July 7th, 2016

Executives from two of the world's top-producing diamond mines revealed to Bloomberg.com how new scanning technology is helping to preserve the largest diamonds during the often-damaging extraction process.

Throughout history, diamond-bearing rock was typically drilled, blasted, hauled and put through crushing machines to get to the gems that may be hiding within. During that process, extremely large diamonds, some weighing hundreds of carats, were often damaged or even pulverized.

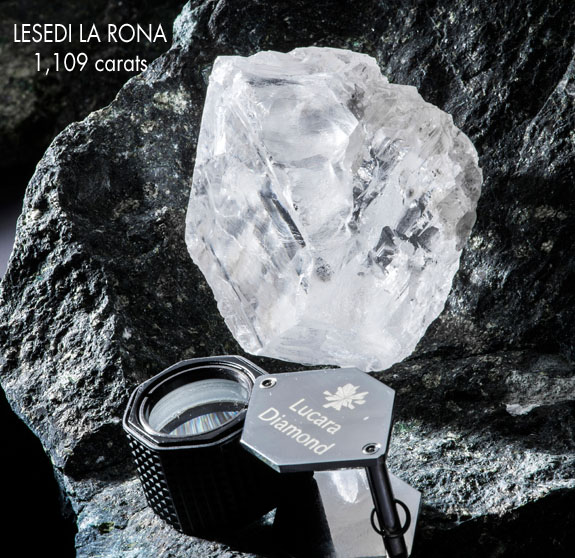

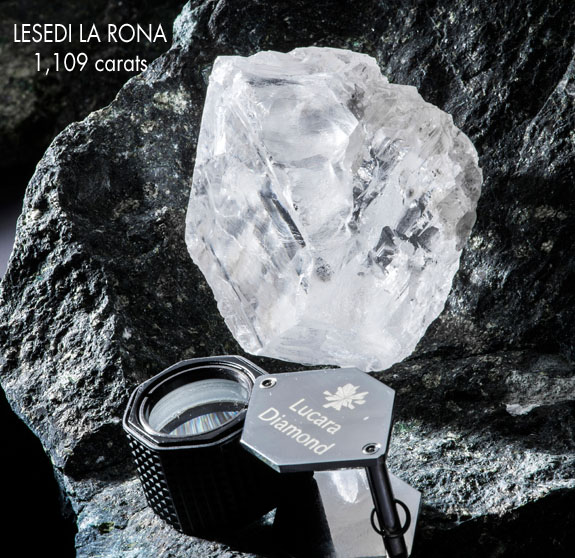

In fact, the highly publicized 1,109-carat Lesedi La Rona diamond was determined to be part of a much larger stone. Lucara CEO William Lamb told Bloomberg.com that it was actually fortunate that a 374-carat chunk broke off the larger stone because Lucara's plant was not designed to process such large material. A 1,500-carat diamond would have been crushed.

“When people say you broke a 1,500-carat diamond, I say we recovered an 1,100-carat diamond,” Lucara CEO William Lamb told Bloomberg.com. “The words ‘mining’ and ‘gentle’ don’t go very well together.”

With the advent of XRT scanners, the mining process is becoming a bit kinder and gentler. As the rock-like material comes down a conveyor belt, the scanners can pick out the diamonds based on their chemical composition. Older scanners used to depend strictly on the stone's ability to reflect light.

The diamond-rich material is then separated from the rubble and moved to a secure area for processing, according to Bloomberg.com.

In the small kingdom of Lesotho, the Letšeng mine produces just 1.6 carats of diamonds for every 100 tons of rock. But despite that tiny output, the mine boasts an average per-carat value of $2,299, the highest in the industry. That's because Letšeng is one of two diamond mines famous for generating the largest and finest-quality diamonds in the world.

The other is the Karowe mine in Botswana, which is the source of Lesedi La Rona, the second-largest gem-quality diamond ever discovered. The gem failed to sell at auction last week when bidding stalled at $61 million. Still, that number was equivalent to $55,000 per carat.

Together, the Karowe and Letšeng mines lay claim to 15 of the 20 largest white diamonds discovered over the past decade, and just about all of them had been part of a larger stone.

“Since the time of the caveman mining hasn’t changed much," Clifford Elphick, chief executive officer of Gem Diamonds Ltd., told Bloomberg.com. "You pulverize the rock and take out what you want. That’s fine in the metals business, but in the diamond business it’s not an appealing technique.”

“We’ve made important inroads, but we certainly haven’t solved the problem because we’re still using the same basic technology,” said Elphick. “What will solve this is a massive technical breakthrough. That is the holy grail for us.”

Gem Diamonds is currently working on a strategy that places XRT scanners earlier in the mining process so the largest diamonds can be identified before the crushing phase.

“We suspect there is the odd 1,000-carat diamond contained within the ore body,” said Gem Diamonds' former COO Alan Ashworth. “But you never know when the diamond is going to be liberated.”

Credits: Image of Lesedi La Rona courtesy of Lucara Diamond Corp. All others courtesy of Gem Diamonds Ltd.

Throughout history, diamond-bearing rock was typically drilled, blasted, hauled and put through crushing machines to get to the gems that may be hiding within. During that process, extremely large diamonds, some weighing hundreds of carats, were often damaged or even pulverized.

In fact, the highly publicized 1,109-carat Lesedi La Rona diamond was determined to be part of a much larger stone. Lucara CEO William Lamb told Bloomberg.com that it was actually fortunate that a 374-carat chunk broke off the larger stone because Lucara's plant was not designed to process such large material. A 1,500-carat diamond would have been crushed.

“When people say you broke a 1,500-carat diamond, I say we recovered an 1,100-carat diamond,” Lucara CEO William Lamb told Bloomberg.com. “The words ‘mining’ and ‘gentle’ don’t go very well together.”

With the advent of XRT scanners, the mining process is becoming a bit kinder and gentler. As the rock-like material comes down a conveyor belt, the scanners can pick out the diamonds based on their chemical composition. Older scanners used to depend strictly on the stone's ability to reflect light.

The diamond-rich material is then separated from the rubble and moved to a secure area for processing, according to Bloomberg.com.

In the small kingdom of Lesotho, the Letšeng mine produces just 1.6 carats of diamonds for every 100 tons of rock. But despite that tiny output, the mine boasts an average per-carat value of $2,299, the highest in the industry. That's because Letšeng is one of two diamond mines famous for generating the largest and finest-quality diamonds in the world.

The other is the Karowe mine in Botswana, which is the source of Lesedi La Rona, the second-largest gem-quality diamond ever discovered. The gem failed to sell at auction last week when bidding stalled at $61 million. Still, that number was equivalent to $55,000 per carat.

Together, the Karowe and Letšeng mines lay claim to 15 of the 20 largest white diamonds discovered over the past decade, and just about all of them had been part of a larger stone.

“Since the time of the caveman mining hasn’t changed much," Clifford Elphick, chief executive officer of Gem Diamonds Ltd., told Bloomberg.com. "You pulverize the rock and take out what you want. That’s fine in the metals business, but in the diamond business it’s not an appealing technique.”

“We’ve made important inroads, but we certainly haven’t solved the problem because we’re still using the same basic technology,” said Elphick. “What will solve this is a massive technical breakthrough. That is the holy grail for us.”

Gem Diamonds is currently working on a strategy that places XRT scanners earlier in the mining process so the largest diamonds can be identified before the crushing phase.

“We suspect there is the odd 1,000-carat diamond contained within the ore body,” said Gem Diamonds' former COO Alan Ashworth. “But you never know when the diamond is going to be liberated.”

Credits: Image of Lesedi La Rona courtesy of Lucara Diamond Corp. All others courtesy of Gem Diamonds Ltd.